***During Covid-19 restrictions and laws, why not have a look at our simple guide in checking your car to keep it roadworthy***

Classic Car Motor oil – have you ever had trouble deciding which type to buy in a shop before your classic (mineral) or modern classic (semi-synthetic) oil change or top up? The different coloured containers, each displaying a unique smattering of letters and numbers, all boasting some form of advanced technology, where does one begin? Do you follow your handbook? Or do you leave it to your local friendly garage to decide? In fact, does it even matter which oil you buy?

Yes. It does.

Oil grade is significant and often its importance is overlooked due to a lack of in depth understanding. There are many brilliant articles on the internet digging deep into the history, development and chemical make up of engine oil, but I want to focus on classic and modern classic cars from the 1960’s to late 1980’s, keeping it simple, using non technical terms, so next time you are stood in front of the oil shelf in the shop you can make an informed choice for your car.

Historically there was only single grade oil. A one trick pony. This one trick pony’s party piece was simply being a certain thickness, technical term, ‘viscosity.’ A number followed by ‘W’ on the can denoted this viscosity, the W standing for ‘winter’. This was the oil’s viscosity rating from cold, when the engine is first started in the morning. But as oil heats up in an engine it becomes thinner, losing its viscosity. Should oil become too thin it can cause poor lubrication and be burnt by the engine. An impossible act to balance then, making the oil thin enough to reach moving parts quickly during a cold start, but ensuring it is thick enough to protect the engine when hot.

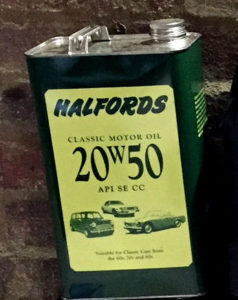

But, technology balanced the act by introducing multigrade oil. With a split personality, a two trick pony was born. This oil had the cold viscosity of one single grade oil and the hot viscosity of another. We now had two numbers sandwiching the ‘W’ on containers. For example, motor oil displaying ’20w50′ simply told us that the oil performed like a ’20w’ single grade when cold and a ’50w’ single grade when hot. It maintained it’s viscosity, making it thin enough to start the car safely from cold, yet keeping enough body to remain effective when hot.

But, technology balanced the act by introducing multigrade oil. With a split personality, a two trick pony was born. This oil had the cold viscosity of one single grade oil and the hot viscosity of another. We now had two numbers sandwiching the ‘W’ on containers. For example, motor oil displaying ’20w50′ simply told us that the oil performed like a ’20w’ single grade when cold and a ’50w’ single grade when hot. It maintained it’s viscosity, making it thin enough to start the car safely from cold, yet keeping enough body to remain effective when hot.

Technology has since brought us multi-trick ponies. The oil I have spoken of so far is mineral based, as mother earth produced it, but we now enjoy semi and fully synthetic oil too. These oils have been fettled by scientists to adjust their chemical make up, the cold start and hot running viscosity finely tuned to suit an engine’s exact requirements. Examples are 10w40 semi synthetic and 5w40 fully synthetic. Both have a lower cold start thickness than the mineral 20w50 oil mentioned earlier- tighter manufacturing tolerances require thinner oil at cold start you see. But note both maintain the hot rating at 40 – this is because tighter tolerances on modern high performance engines produce more heat, and thus the oil needs to keep a closer eye on it’s viscosity when hot, extremely hot for that matter. The epitome of a modern oil doing just this is the grade the BMW E46 M3 and Maserati 3200 run on. Enter 10w60 fully synthetic. Nice and thin to start up from cold, but the number 60 ensures that it never becomes too thin to damage the intricately designed internals of these extremely hot running high output power-plants.

Living and working inside a car’s engine, oil endures a heat cycle from cold to hot as you start and drive the car, and hot to cold once you stop driving and turn the engine off. Circulating through gaps, channels, filters, galleries, holes, over and in-between moving parts at varying pressure, oil works hard. Not to mention the constant exposure to extreme heat and corruption from the poisonous fumes, soot and water produced by the engine’s combustion process. Oil has a tough time. The oil’s performance, health and life span are very much determined by its working environment, including external factors such as climate and types of journey the car undertakes.

And thus, manufacturers tend to make a few suggestions in the handbook for an oil grade and change interval, taking into account the known tolerances and requirements of their new engine, along with possible climate and journey types, leaving you as the owner to evaluate your own unique situation selecting the most suitable suggestion for you. For example a car living in the minus temperatures of Iceland may require the thinner multigrade oil listed in the handbook than the same model of car living in a warm climate like Africa.

But, each individual car over time, especially classic cars, having aged and lived with varying owners, various climates, differing driving styles, maintenance procedures and perhaps even having an engine rebuild under their belt, will have created a unique working environment for their oil. Tolerances change with wear and tear, altering gaps, a build up of soot and oil sludge changes the diameter of galleries and the car may have spent the first decade of its life enduring short stop and start journeys, or indeed run a few different grades of oil over its lifetime before your ownership.

So, having digested the above, you can now drop a ‘know it all’ sentence into a pub conversation, and perhaps de-code the label on an oil container. But, Trade Classic readers, I hear you shout, how the hell does this help me with my car?

As best practice I hope you are using the grade of oil recommended by your trusty handbook, however you must bear in mind your classic car oil’s working environment is likely to be very different from the day it left the factory. But by making a date with your classic car to spend some quality time getting to know the new environment, you can make an informed evaluation of your current oil grade and whether it is time to vary it up or down slightly. As well as when to change it and how to perhaps alter your driving patterns. All in turn giving your chosen oil the best quality of working life – and we all know a healthy working environment makes staff perform better.

How to evaluate the current grade of oil you use and get to know its working environment.

Begin the process about 100 miles since you last topped up your oil level to the maximum, providing it was checked when hot and on level ground. Also ensure your 60’s to 80’s classic car has stood overnight. Armed with a note pad and pen to record your findings during each of the following steps, along with a top up bottle containing the car’s current grade of oil, a funnel and a rag, head over to your pride and joy.

Begin the process about 100 miles since you last topped up your oil level to the maximum, providing it was checked when hot and on level ground. Also ensure your 60’s to 80’s classic car has stood overnight. Armed with a note pad and pen to record your findings during each of the following steps, along with a top up bottle containing the car’s current grade of oil, a funnel and a rag, head over to your pride and joy.

1. Open the bonnet. Now start the engine, watching the oil pressure warning light if you have one, whilst listening intently for rattles from the engine for the first few seconds. How long did the oil light take to extinguish? Were there any noises? If you have oil pressure gauge take a note of the reading now while the car is idling. Close the bonnet.

2. Drive the car for at least half an hour to warm it up and park up on a flat surface, switching the engine off. Allow the car to stand for five minutes. Pop the bonnet and check the oil level, topping up to the maximum marker if necessary. Check your dipstick. Is it kinked or bent? I ask because sometimes if this is the case it can give a false oil level reading and you can over or under fill your car, both harmful in their own way. Note down how much was required and the car’s current mileage.

3. Drive home taking note of the oil pressure gauge’s reading at higher revs and at warm idle. When stationary, watch the rear view mirror, then rev your engine a few times. Can you see blue smoke? As you arrive home leave your car running and head round to the exhaust, is there any blue smoke at idle? Can you smell oil?

4. Leaving the car running, pop the bonnet and listen out for any strange noises, such as whirring, thumping or rattling noises. If you have any, trace them carefully with your ears to locate the approximate culprit location wise on the engine. Can you smell oil? Can you see any oil sludge or leaks gently oozing out of the engine gaskets or pipework?

5. Close the bonnet and turn your car off. Now look at your notes…and compare your oil gauge readings with those stated in your handbook. Do they match well?

*If your engine produces any knocking, thumping or rattling noises when warm, exhibits blue smoke, low oil pressure and a substantial top up was required, you can try your luck going for a thicker oil, but I really suggest a trip to your local friendly garage for investigation.

If the oil light went out within a few seconds, the actual pressures match your handbook fairly well, there was no rattle from start up, no blue smoke at all and oil top up was minimal, I think all is just fine. Your oil grade is probably correct and matches the environment it operates in.

However, if there was rattle at start up, with either the oil pressure light taking longer than the standard few seconds to extinguish and or/the oil pressure gauge reading lower than it should at cold start idle, but the warm tests and oil level were acceptable, your oil may simply be a little too thick. If you are running a 20w50 for example, a 15w40 may suit cold start better, or even a 10w40.

Alternatively, if you did not experience a rattle from start up and the oil pressure and/or light behaved perfectly from cold, but when warm you noticed blue smoke and a fairly substantial top up was required, your oil may be too thin. The car is burning it. If you are running a 15w40, perhaps try 20w50. It could be a sign that components in your engine are worn but there is no harm in trying a thicker oil first.

Should you spot sludge and oil residue oozing out of gaskets and pipes, it could be genuine oil leaks caused by age or it could be down to oil that is too thin yet again. Try a slightly thicker grade and see how you progress. But at this point I think it is best to get to know your car a little better, because oil consumption, higher than normal oil pressure, leaks and sludge oozing out along with oil smell might not be solely down to your oil grade. It could be its working environment…

PCV. Positive Crankcase Ventilation. Remember all the nasty fumes, deposits and water produced by the combustion process? This system allows them to exit the engine, either venting some of it to atmosphere or reinstating the fumes into the air inlet for the engine to burn after having drawn them out of the engine through a filter and series of vent pipes. The system relies heavily on the oil becoming hot enough to boil out the impurities and water. But the system can become blocked causing pressure to build up in the engine, in turn increasing oil pressure and creating leaks. The oil will deteriorate faster than normal too.

And when the system malfunctions in a different way, it can sometimes even suck oil out of the engine increasing oil consumption heavily. So a correctly functioning PCV system in top order is one of the most important components of the oil’s working environment.

Does your engine run well? Is it misfiring? This is not good for your oil at all, or your engine for that matter. Each time a cylinder fails to fire but receives fuel, that fuel will wash the oil away from the inside walls of the cylinder that should lubricate the piston moving up and down, technical term ‘bore wash’. The un-burnt fuel mixes into the oil contaminating it, thinning it out and increasing its fluid volume.

Is your car running rich, pouring way to much fuel into the cylinders? I believe this can have the same effect as a misfire.

Does your classic car maintain its engine temperature correctly? If not, the oil may be under unnecessary heat stress.

Do you have after market exhausts? Does any of the pipework run close to the sump? The extra heat from exhausts can sometimes cause oil to become hotter than it should be in your engine, and this is never a good thing.

If any of the above is suspect, now is the time to put it right, before a fresh oil and filter change. If you are a competent home mechanic use your Haynes manual or a guide from an owners forum and get cracking cleaning the components of your PCV system, replacing any brittle or blocked pipes along the way and the air filter element too. Sort that misfire. Tweak the fuelling. Fix any significant leaks. Treat the exhaust to good quality heat wrap. Give the cooling system an overhaul. And finally, assuming you have not already drained the oil when fixing leaks, warm your classic beauty up and give her an oil and filter change with your chosen grade, whether it be the original you were running or a grade slightly up or down from the original based on the test results earlier. Remember to replace the sump plug and washer too. Alternatively ask your local friendly garage to carry all of the work out for you.

If any of the above is suspect, now is the time to put it right, before a fresh oil and filter change. If you are a competent home mechanic use your Haynes manual or a guide from an owners forum and get cracking cleaning the components of your PCV system, replacing any brittle or blocked pipes along the way and the air filter element too. Sort that misfire. Tweak the fuelling. Fix any significant leaks. Treat the exhaust to good quality heat wrap. Give the cooling system an overhaul. And finally, assuming you have not already drained the oil when fixing leaks, warm your classic beauty up and give her an oil and filter change with your chosen grade, whether it be the original you were running or a grade slightly up or down from the original based on the test results earlier. Remember to replace the sump plug and washer too. Alternatively ask your local friendly garage to carry all of the work out for you.

Now your fresh oil has a excellent working environment, with all the vital tools present and functioning, it is time to spend the next 500 miles making the best of this of new and shiny workplace. Time for the oil to do some work!

Over the next 500 miles, at the start of each 100 mile interval, note down the mileage, check the oil level once warm on a flat surface, topping up as necessary, noting down how much oil your car took if any. Keep an eye on the oil pressure gauge and light to ensure that are behaving as they should.

Avoid starting the engine from cold and turning it off it straight away. Once started, warm it up fully and take it on a long drive, remembering the PCV system works best when it boils the impurities from the oil. Your fresh oil with your correctly functioning PCV system will clean the engine a little too. Try and drive the car regularly, on longer journeys as opposed to shorter ones, every week at the minimum. Starting regularly should keep an oil film on top of engine components and inside galleries making cold start friendlier to your engine.

After 500 miles, look at your notes. If the oil consumption was acceptable for your car, for example it has used half a litre in 500 miles (an older classic car is allowed to burn oil!), blue smoke and rattles are non existent and gauges are fine, stick with the same grade and complete an oil and filter change. Sometimes oil choice takes a little bit of experimenting so you can always move slightly up or down at this stage if you think you can find a better match of oil for the working environment. Just monitor the usual suspects above until the next standard schedule oil change.

And when should that next oil change take place? Well, given that classic cars often get used less but are likely to undertake longer journeys getting the engine nice and warm, I think a sensible bet is every 3000 miles or once a year, whichever comes first. And when changing the oil it is always advisable to have the oil at its hottest, and let the it drain out completely, renewing the filter each time. No harm in changing the sump plug and washer each time too, for the sake of a few quid, who wants leaks or a sump nut that next oil change doesn’t want to come out?

As for additives, being honest I have never actually used anything like a flushing agent, my view is they can dislodge perfectly formed harmless sludge to block up part of the oil circuit that could cause problems…but that is my opinion and my opinion only, I welcome thoughts on this, I love learning new and wonderful tips for classic car maintenance.

To summarize, make sure your engine is good to its oil, and thus the oil will protect it in return. I guess looking after a classic car’s engine is like running a successful business – welcome a suitable employee on board, with a proper induction, setting up a great working space with effective tools, and treat them well. In turn, they will be the best employee they can, and that’s fabulous news for your business.

And thus when Engine & Co welcomes Castrol GTX onto its payroll, although that employee is not staying forever, it is vital to get the best out of them when they are there, ensuring that they leave the working environment in perfect order for the next superb employee.

Oh yeah, and if you like my articles then you can have them delivered straight to your lovely inbox – simply subscribe to my blog.

MIKE ATWAL

This article was written and published by Mike Atwall. Mike works for Trade Classics as an in-house journalist and copywriter and has many years’ experience in the classic car sector – for over 8 years he was the General Manager of the Classic Car Club in London and responsible for a fleet of over 100 cars worth multi-million pounds. So there’s not much Mike doesn’t know about makes, models, maintenance and idiosyncrasies of these old cars. Mike’s a true petrol head with a deep passion for the classics and he loves to talk cars all day, so why not write a reply on this article below.

Google+

Categories: car auction, Classic Car Maintenance, Mike Atwal

Hey Bro!! Long time!! Excellent article!! You back in the UK now?

Kindly let me know the best engine oil grade to be used for my 1949 model Vauxhall Velox , England car .

Not much use for anyone except someone who has just bought their first classic. I don’t know when this was written but I can’t believe there is no mention of ZDDP, its reducing levels in recent years, and the damaging effects this has on classic engines.

Not all classic engines require a high level of ZDDP in the engine oil. Engines with roller tappets don’t for example, but flat tappets and OHC engines often do. You can have too much ZDDP also!

I know and I know. But to not mention it at all is a major omission, which is why I raised it!

I agree, flat tappet cams need zddp and moly and other additives that have been slowy reduced over the years from 1600 to 2000 ppm to 800 to 900.